The longer you continue to study something in detail, the more important it becomes to step back, take stock and analyze the big picture. I’ve been studying anatomy for an extended period at this point. I started with the skeleton last August and have been sticking with daily practice, albeit with a few breaks here and there for holidays and vacations.

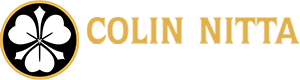

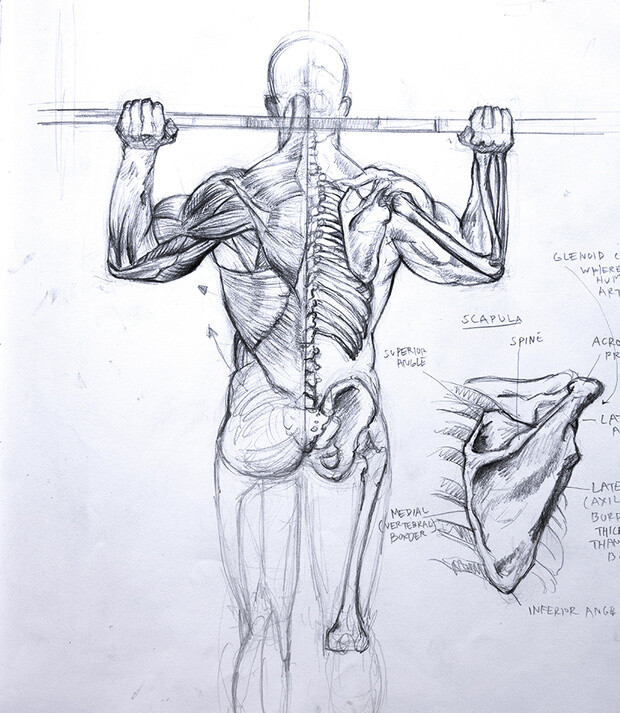

For the past few months I’ve had a steady diet of highly detailed muscular breakdown drawings from books that I then try to recall with memory studies. I make a lot of notes as I move through these studies, with specific breakdowns of where each muscle originates and inserts and how they change through motion and stress. It’s an exhausting, yet fascinating subject!

Sometime in the beginning of my pursuits I started an anatomy specific sketchbook with the goal of filling it up completely. Having this sketchbook has been a great incentive to keep going and track my progress. You can see here that it’s getting halfway full, with all the pages I’ve drawn on looking considerably gnarlier as they are covered in graphite and workable fixative.

As I continued to study musculature this past March and April, I got around to covering all the major groups and the arms and legs from the major angles. There is so much to discover here and I found myself wanting to know more about the individual actions and movements of each distinct muscle and every time I did so, there was more to think about.

This is a great way to learn about specific details of human anatomy. But how does it apply to illustration and character design? What can we take from this micro study and apply to broad concepts?

To aid in answering this question, I’ve begun to take a closer look at one of the classic books on anatomy in illustration: Figure Drawing for All It’s Worth by Andrew Loomis.

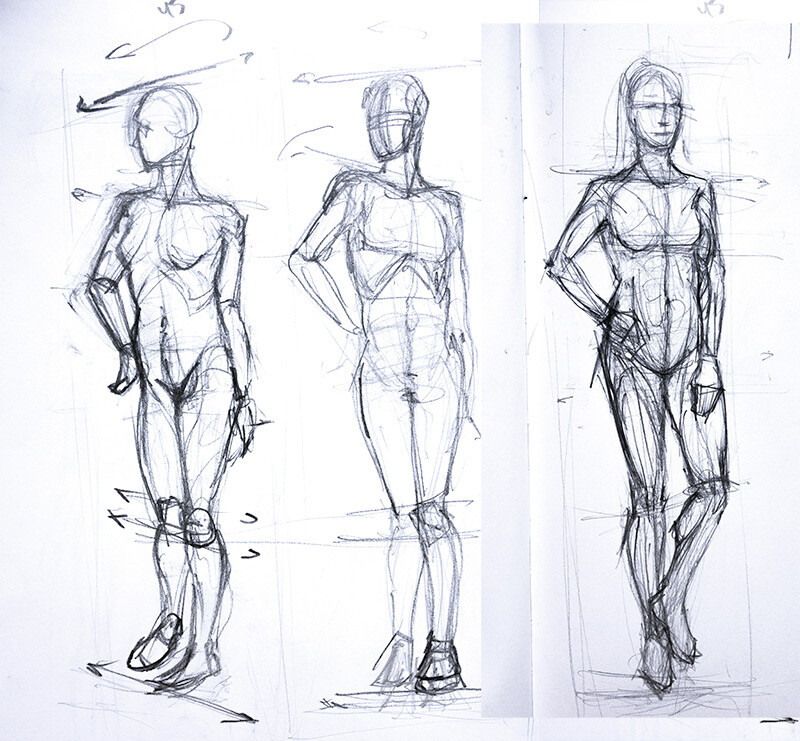

It turns out that the best way to start applying these specific lessons is to turn to the most general of drawing ideas: the mannequin.

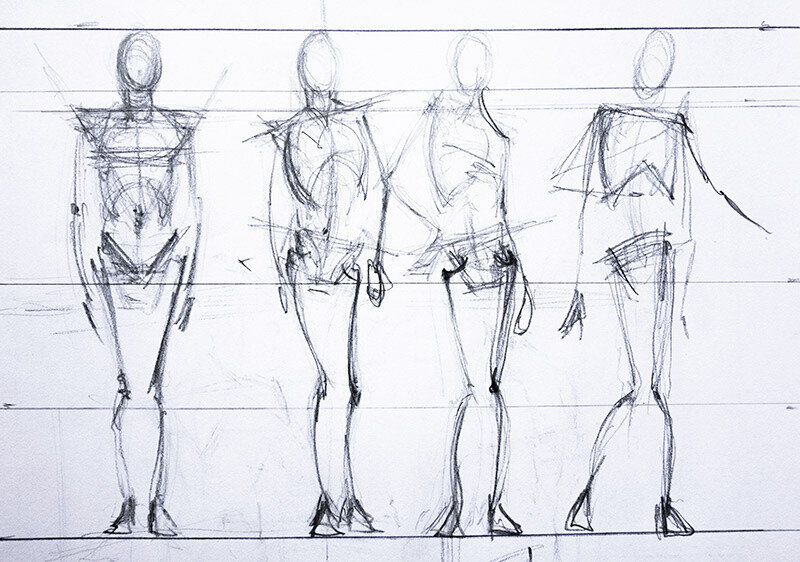

The mannequin is essentially a very stripped down version of the anatomical models I’ve been drawing this whole time. The general idea is that the mannequin allows a simplification of all the complexities that are happening in human anatomy and just covers the simple basics with a straightforward proportional scale.

I have seen this mannequin technique, but it never really gelled for me because I was unaware of the base structure that it is founded upon. Essentially, the mannequin draws upon the shape of the skeleton, but then extrapolates it out for movement, attitude and gesture.

I’ve done dozens of these skeletal studies at this point. When I came across the mannequin idea again in Loomis’ book, it finally clicked. I understood his overall proportional scale because I saw how it matched the actual skeleton.

This is what I mean when moving from “micro to macro” in terms of artistic anatomy. The micro level of detail, such as the relationship between the the deltoid, triceps and biceps – is just as important as the macro level, such as a basic mannequin that is used in establishing overall proportion and gesture.

This micro versus macro dichotomy is what makes anatomy such a tricky subject for so many artists. I hope to sharpen both points of view as I continue to make discoveries in my endless anatomy quest!